Using R for bioassessment data: What, why, and how

Lesson Outline

Lesson Exercises

Goals and Motivation

R is a language for statistical computing as well as a general purpose programming language. Increasingly, it has become one of the primary languages used in data science and for data analysis across many of the natural sciences.

The goals of this training are to expose you to fundamentals and to develop an appreciation of what’s possible with this software. We also provide resources that you can use for follow-up learning on your own. You should be able to answer these questions at the end of this session:

- What is R and why should I use it?

- Why would I use RStudio and RStudio projects?

- How can I write, save, and run scripts in RStudio?

- Where can I go for help?

- What are the basic data structures in R?

- How do I import data?

Why should I invest time in R?

There are many programming languages available and each has it’s specific benefits. R was originally created as a statistical programming language but now it is largely viewed as a ‘data science’ language. Why would you invest time in learning R compared to other languages?

- The growth of R as explained in the Stack Overflow blog, IEEE rating

R is also an open-source programming language - not only is it free, but this means anybody can contribute to it’s development. As of 2020-01-05, there are 15316 supplemental packages for R on CRAN!

RStudio

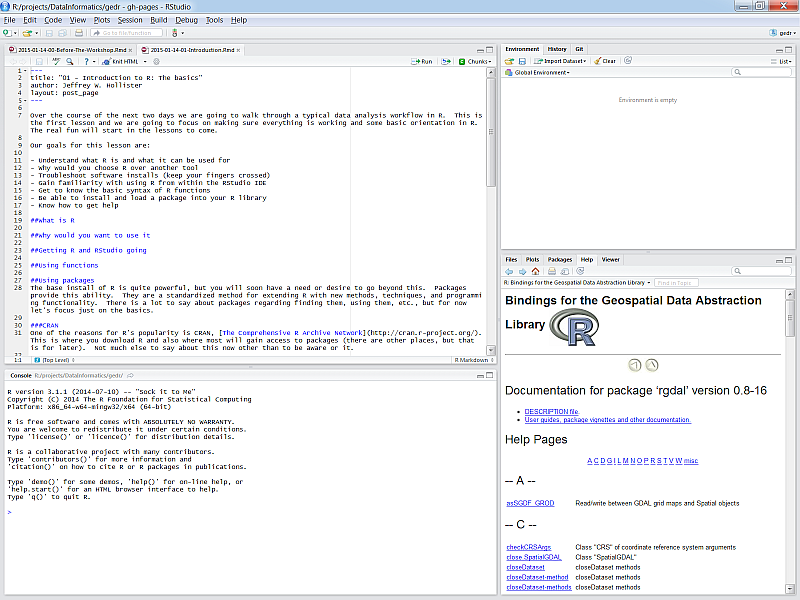

In the old days, the only way to use R was directly from the Console - this is a bare bones way of running R only with direct input of commands. Now, RStudio is the go-to Interactive Development Environment (IDE) for R. Think of it like a car that is built around an engine. It is integrated with the console (engine) and includes many other features to improve the user’s experience, such as version control, debugging, dynamic documents, package manager and creation, and code highlighting and completion.

Let’s get familiar with RStudio before we go on.

Open R and RStudio

If you haven’t done so, download and install RStudio from the link above. After it’s installed, find the RStudio shortcut and fire it up (just watch for now). You should see something like this:

There are four panes in RStudio:

- Source

- console

- Environment, History, etc.

- Files, plots, etc.

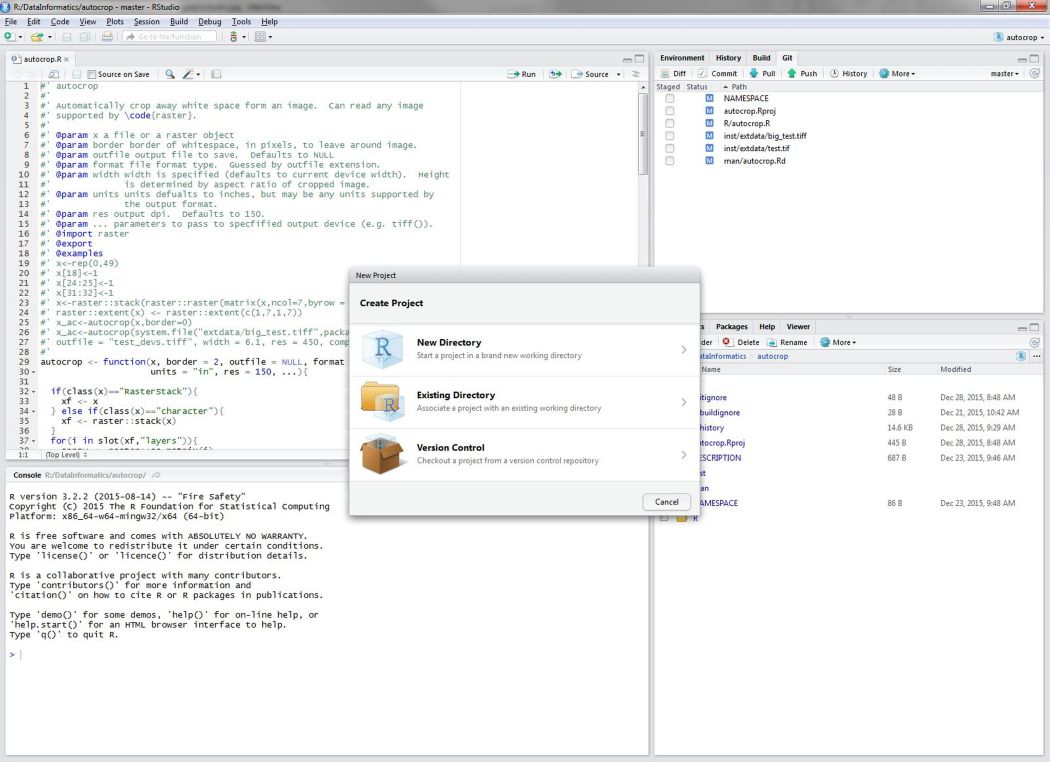

RStudio projects

I strongly encourage you to use RStudio projects when you are working with R. The RStudio project provides a central location for working on a particular task. It helps with file management and is portable because all the files live in the same project. RStudio projects also remember history - what commands you used and what data objects are in your enviornment.

To create a new project, click on the File menu at the top and select ‘New project…’

Now we can use this project for our data and any scripts we create.

Scripting

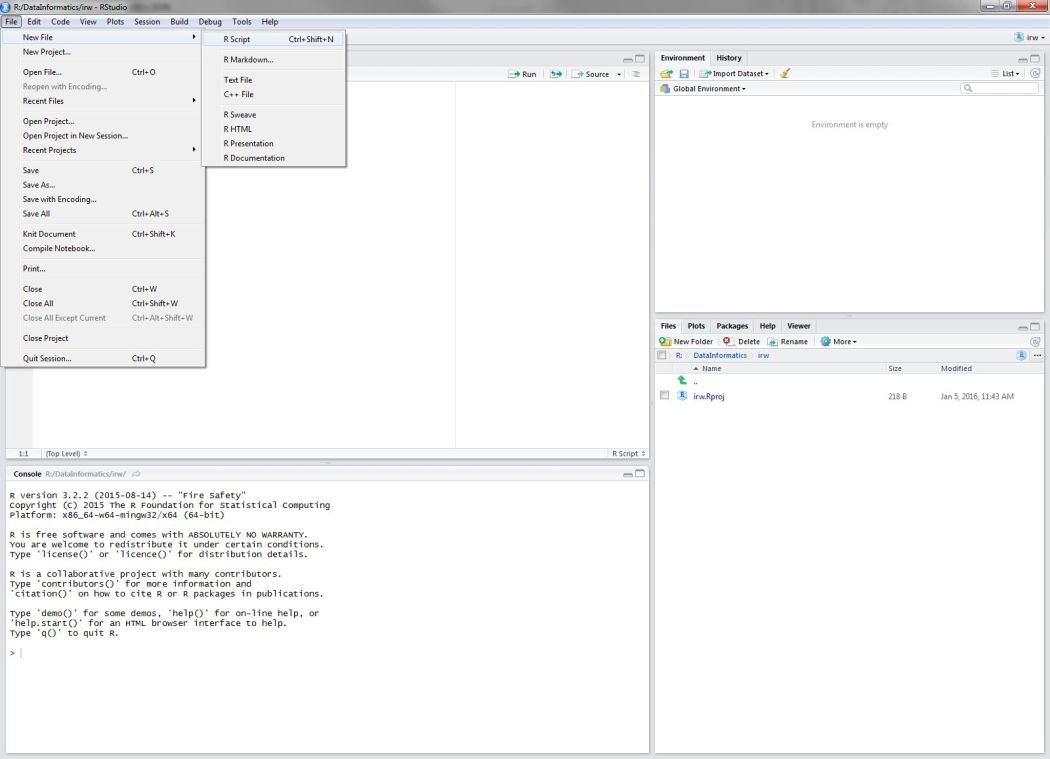

In most cases, you will not enter and execute code directly in the console. Code can be written in a script and then sent directly to the console when you’re ready to run it. The key difference here is that a script can be saved and shared.

Open a new script from the File menu…

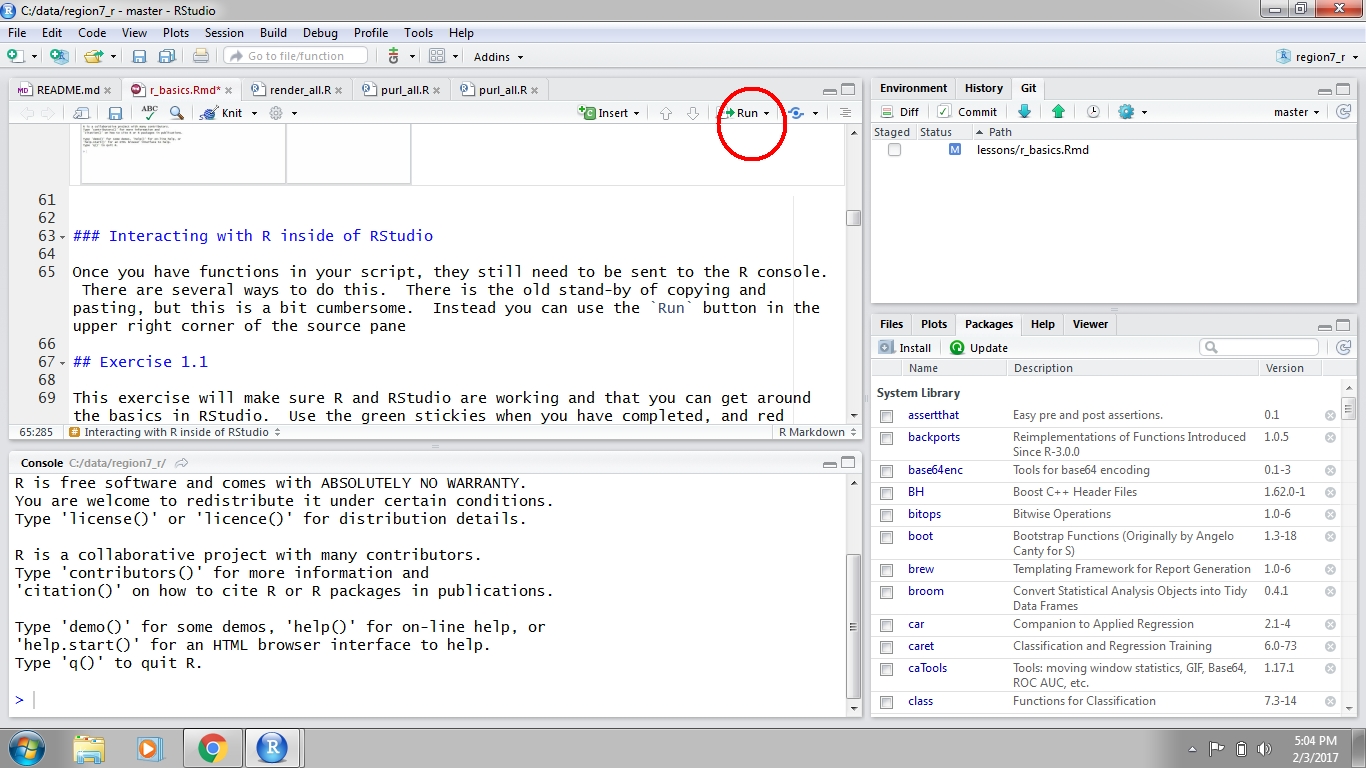

Executing code in RStudio

After you write your script it can be sent to the Console to run the code in R. Any variables you create in your script will not be available in your working environment until this is done. There are two ways to send code to the console. First, you can hit the Run button at the top right of the scripting window. Second, and preferred, you can use ctrl+enter (cmd+enter on a Mac). Both approaches will send the selected line to the console, then move to the next line in your script. You can also highlight and send an entire block of code.

What is the environment?

There are two outcomes when you run code. First, the code will simply print output directly in the console. Second, there is no output because you have stored it as a variable (we’ll talk about variable assignment later). Output that is stored is actually saved in the environment. The environment is the collection of named objects that are stored in memory for your current R session. Anything stored in memory will be accessible by it’s name without running the original script that was used to create it.

Exercise 1

This exercise will make sure R and RStudio are working and that you can get around the basics in RStudio. Use the blue stickies when you have completed, and red stickies if you are running into problems.

Start RStudio: To start both R and RStudio requires only firing up RStudio. RStudio should be available from All Programs at the Start Menu. Fire up RStudio.

Create a new project. Name it “cabw_r_workshop”. We will use this for the rest of the workshop.

Create a new “R Script” in the Source Pane, save that file into your newly created project and name it “cabw_script.R”. It’ll just be a blank text file at this point.

Add in a comment line to separate this section. It should look something like:

# Exercise 1: Just Getting used to RStudio and Scripts.Lastly, we need to get this project set up with some example data for our exercises. You should have downloaded this already, but if not, the data are available here. The data are in a zipped folder. Download the file to your computer (anywhere). Create a folder in your new project named

dataand extract the files into this location.

R language fundamentals

The basic syntax of a function follows the form: function_name(arg1, arg2, ...).

With the base install, you will gain access to many functions (2682, to be exact). Some examples:

# print

print('hello world!')## [1] "hello world!"# sequence

seq(1, 10)## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10# random numbers

rnorm(100, mean = 10, sd = 2)## [1] 15.029863 9.504855 8.495452 10.735446 10.147796 11.155330 8.059115

## [8] 11.183410 7.636009 13.084366 8.176553 11.556673 10.870692 11.791386

## [15] 9.911749 10.933113 9.625723 8.604161 10.833915 11.185085 14.206069

## [22] 9.738960 9.776363 10.969604 8.976868 9.456172 8.813325 13.220348

## [29] 6.255681 11.233555 8.403339 7.312847 10.753612 11.922396 7.476220

## [36] 9.773417 9.397070 9.161689 9.166348 15.131267 9.604910 10.148325

## [43] 8.029399 10.743290 10.391792 11.176691 7.758645 11.497596 10.710358

## [50] 11.530855 6.672026 9.071498 12.772938 10.127421 11.664292 9.122088

## [57] 7.476628 9.210463 8.123345 9.385807 9.547906 10.980478 10.760303

## [64] 11.153934 9.599652 9.204581 6.608733 6.840840 10.146724 9.660492

## [71] 9.772478 7.465127 9.246003 11.814800 9.514882 7.540854 9.893602

## [78] 10.258499 8.565367 12.852896 12.131330 10.838035 10.210317 12.011242

## [85] 9.407239 12.972351 10.379250 8.412654 9.893556 13.424042 8.356429

## [92] 11.928442 10.658048 7.511820 12.253362 10.378984 10.950845 9.504111

## [99] 6.661446 12.076945# average

mean(rnorm(100))## [1] -0.006075047# sum

sum(rnorm(100))## [1] -7.906235Very often you will see functions used like this:

my_random_sum <- sum(rnorm(100))In this case the first part of the line is the name of an object. You make this up. Ideally it should have some meaning, but the only rules are that it can’t start with a number and must not have any spaces. The second bit, <-, is the assignment operator. This tells R to take the result of sum(rnorm(100)) and store it in an object named, my_random_sum. It is stored in the environment and can be used by just executing it’s name in the console.

my_random_sum## [1] -8.787773With this, you have the very basics of how we write R code and save objects that can be used later.

Packages

The base install of R is quite powerful, but you will soon have a need or desire to go beyond this. Packages provide this ability. They are a standardized way of extending R with new methods, techniques, and programming functionality. There is a lot to say about packages regarding finding them, using them, etc., but for now let’s focus just on the basics.

CRAN

One of the reasons for R’s popularity is CRAN, The Comprehensive R Archive Network. This is where you download R and also where most will gain access to packages (there are other places, but that is for later). Not much else to say about this now other than to be aware of it. As of 2020-01-05, there are 15316 on CRAN!

Installing packages

When a package gets installed, that means the source code is downloaded and put into your library. A default library location is set for you so no need to worry about that. In fact, on Windows most of this is pretty automatic. Let’s give it a shot.

Exercise 2

We’re going to install some packages from CRAN that will give us the tools for our workshop today. We’ll use the tidyverse, sf, mapview, viridis, and USAboundaries packages. Later, we’ll explain in detail what each of these packages provide.

At the top of the script you just created, type the following functions.

# install packages from CRAN install.packages("tidyverse") install.packages("sf") install.packages("mapview") install.packages("viridis") install.packages("USAboundaries")Select all the lines by clicking and dragging the mouse pointer over the text.

Send all the commands to the console using

ctrl+enter. You should see some text output on the console about the installation process. The installation may take a few minutes so don’t be alarmed.After the packages are done installing, verify that there were no errors during the process (this should be pretty obvious, i.e., error text in big scary red letters).

Load the packages after they’ve installed.

library("tidyverse") library("sf") library("mapview") library("viridis") library("USAboundaries")

Getting Help

Being able to find help and interpret that help is probably one of the most important skills for learning a new language. R is no different. Help on functions and packages can be accessed directly from R, can be found on CRAN and other official R resources, searched on Google, found on StackOverflow, or from any number of fantastic online resources. I will cover a few of these here.

Help from the console

Getting help from the console is straightforward and can be done numerous ways.

# Using the help command/shortcut

# When you know the name of a function

help("print") # Help on the print command

?print # Help on the print command using the `?` shortcut

# When you know the name of the package

help(package = "sf") # Help on the package `dplyr`

# Don't know the exact name or just part of it

apropos("print") # Returns all available functions with "print" in the name

??print # shortcut, but also searches demos and vignettes in a formatted pageOfficial R Resources

In addition to help from within R itself, CRAN and the R-Project have many resources available for support. Two of the most notable are the mailing lists and the task views.

- R Help Mailing List: The main mailing list for R help. Can be a bit daunting and some (although not most) senior folks can be, um, curmudgeonly…

- R-sig-ecology: A special interest group for use of R in ecology. Less daunting than the main help with participation from some big names in ecological modelling and statistics (e.g., Ben Bolker, Gavin Simpson, and Phil Dixon).

- Environmetrics Task View: Task views are great in that they provide an annotated list of packages relevant to a particular field. This one is maintained by Gavin Simpson and has great info on packages relevant to much of the work at EPA.

- Spatial Analysis Task View: One I use a lot that lists all the relevant packages for spatial analysis, GIS, and Remote Sensing in R.

Google and StackOverflow

While the resources already mentioned are useful, often the quickest way is to just turn to Google. However, a search for “R” is a bit challenging. A few ways around this. Google works great if you search for a given package or function name. You can also search for mailing lists directly (i.e. “R-sig-geo”), although Google often finds results from these sources.

Blind googling can require a bit of strategy to get the info you want. Some pointers:

- Always preface the search with “r”

- Understand which sources are reliable

- Take note of the number of hits and date of a web page

- When in doubt, search with the exact error message (see here for details about warnings vs errors)

One specific resource that I use quite a bit is StackOverflow with the ‘r’ tag. StackOverflow is a discussion forum for all things related to programming. You can then use this tag and the search functions in StackOverflow and find answers to almost anything you can think of. However, these forums are also very strict and I typically use them to find answers not to ask questions.

Other Resources

As I mentioned earlier, there are TOO many resources to list here and everyone has their favorites. Below are just a few that I like.

- R For Cats: Basic introduction site, meant to be a gentle and light-hearted introduction

- Advanced R: Web home of Hadley Wickham’s new book. Gets into more advanced topics, but also covers the basics in a great way.

- CRAN Cheatsheets: A good cheat sheet from the official source

- RStudio Cheatsheets: Additional cheat sheets from RStudio. I am especially fond of the data wrangling one.

Data structures in R

Now that you know how to get started in R and where to find resources, we can begin talking about R data structures. Simply put, a data structure is a way for programming languages to handle information storage.

There is a bewildering amount of formats for storing data and R is no exception. Understanding the basic building blocks that make up data types is essential. All functions in R require specific types of input data and the key to using functions is knowing how these types relate to each other.

Vectors (one-dimensional data)

The basic data format in R is a vector - a one-dimensional grouping of elements that have the same type. These are all vectors and they are created with the c function:

dbl_var <- c(1, 2.5, 4.5)

int_var <- c(1L, 6L, 10L)

log_var <- c(TRUE, FALSE, T, F)

chr_var <- c("a", "b", "c")The four types of atomic vectors (think atoms that make up a molecule aka vector) are double (or numeric), integer, logical, and character. For most purposes you can ignore the integer class, so there are basically three types. Each type has some useful properties:

class(dbl_var)## [1] "numeric"length(log_var)## [1] 4These properties are useful for not only describing an object, but they define limits on which functions or types of operations that can be used. That is, some functions require a character string input while others require a numeric input. Similarly, vectors of different types or properties may not play well together. Let’s look at some examples:

# taking the mean of a character vector

mean(chr_var)

# adding two numeric vectors of different lengths

vec1 <- c(1, 2, 3, 4)

vec2 <- c(2, 3, 5)

vec1 + vec22-dimensional data

A collection of vectors represented as a single data object are often described as two-dimensional data. A more common way of storing two-dimensional data is in a data frame (i.e., data.frame). Think of them like your standard spreadsheet, where each column describes a variable and rows link observations between columns. Here’s a simple example:

ltrs <- c('a', 'b', 'c')

nums <- c(1, 2, 3)

logs <- c(T, F, T)

mydf <- data.frame(ltrs, nums, logs)

mydf## ltrs nums logs

## 1 a 1 TRUE

## 2 b 2 FALSE

## 3 c 3 TRUEThe only constraints required to make a data frame are:

Each column contains the same type of data

The number of observations in each column is equal.

Getting your data into R

It is the rare case when you manually enter your data in R, not to mention impractical for most datasets. Most data analysis workflows typically begin with importing a dataset from an external source. Literally, this means committing a dataset to memory (i.e., storing it as a variable) as one of R’s data structure formats.

Flat data files (text only, rectangular format) present the least complications on import because there is very little to assume about the structure of the data. On import, R tries to guess the data type for each column and this is fairly unambiguous with flat files. The base installation of R comes with some easy to use functions for importing flat files, such as read.table() and read.csv().

Exercise 3

Now that we have the data downloaded and extracted to our data folder, we’ll use read.csv to import two files.

Type the following in your script. Note the use of relative file paths within your project.

cscidat <- read.csv('data/cscidat.csv', stringsAsFactors = F) ascidat <- read.csv('data/ascidat.csv', stringsAsFactors = F)Send the commands to the console with

ctrl+enter.Verify that the data imported correctly by viewing the first six rows of each dataset. Use the

head()function directly in the console, e.g.,head(cscidat)

Let’s explore the datasets a bit. There are many useful functions for exploring the characteristics of a dataset. This is always a good idea when you first import something.

# get the dimensions

dim(cscidat)## [1] 1613 10dim(ascidat)## [1] 2585 3# get the column names

names(cscidat)## [1] "SampleID_old" "StationCode" "New_Lat" "New_Long"

## [5] "COMID" "E" "OE" "pMMI"

## [9] "CSCI" "SampleID_old.1"names(ascidat)## [1] "id" "site_type" "ASCI"# see the first six rows

head(cscidat)## SampleID_old StationCode New_Lat New_Long COMID E

## 1 000CAT148_8.10.10_1 000CAT148 39.07523 -119.8994 8942501 16.05804

## 2 000CAT228_8.10.10_1 000CAT228 39.07307 -119.9201 8942503 16.08960

## 3 102PS0139_8.9.10_1 102PS0139 41.99595 -122.9597 23936337 15.46439

## 4 103CDCHHR_9.14.10_1 103CDCHHR 41.78890 -124.0778 22226836 21.10443

## 5 103FC1106_7.15.14_1 103FC1106 41.93407 -124.1081 22226634 16.83757

## 6 103FCA168_7.24.13_1 103FCA168 41.64962 -124.0912 22226990 19.07408

## OE pMMI CSCI SampleID_old.1

## 1 0.9309977 1.0449580 0.9879779 000CAT148_8.10.10_1

## 2 0.9726777 0.9896232 0.9811505 000CAT228_8.10.10_1

## 3 1.0896002 1.0535386 1.0715694 102PS0139_8.9.10_1

## 4 1.0898184 1.0834653 1.0866419 103CDCHHR_9.14.10_1

## 5 1.0779468 0.9163731 0.9971599 103FC1106_7.15.14_1

## 6 1.0931064 1.0335179 1.0633122 103FCA168_7.24.13_1head(ascidat)## id site_type ASCI

## 1 000CAT148_8.10.10_1 Reference 1.1950555

## 2 000CAT228_8.10.10_1 Reference 1.1514480

## 3 102PS0139_8.9.10_1 Intermediate 0.9345882

## 4 102PS0177_8.28.12_1 Reference 1.1965128

## 5 102PS0177_8.28.12_2 Reference 1.2091360

## 6 103CDCHHR_9.14.10_1 Reference 0.8369236# get the overall structure

str(cscidat)## 'data.frame': 1613 obs. of 10 variables:

## $ SampleID_old : chr "000CAT148_8.10.10_1" "000CAT228_8.10.10_1" "102PS0139_8.9.10_1" "103CDCHHR_9.14.10_1" ...

## $ StationCode : chr "000CAT148" "000CAT228" "102PS0139" "103CDCHHR" ...

## $ New_Lat : num 39.1 39.1 42 41.8 41.9 ...

## $ New_Long : num -120 -120 -123 -124 -124 ...

## $ COMID : int 8942501 8942503 23936337 22226836 22226634 22226990 22227592 22226948 22226612 22226750 ...

## $ E : num 16.1 16.1 15.5 21.1 16.8 ...

## $ OE : num 0.931 0.973 1.09 1.09 1.078 ...

## $ pMMI : num 1.045 0.99 1.054 1.083 0.916 ...

## $ CSCI : num 0.988 0.981 1.072 1.087 0.997 ...

## $ SampleID_old.1: chr "000CAT148_8.10.10_1" "000CAT228_8.10.10_1" "102PS0139_8.9.10_1" "103CDCHHR_9.14.10_1" ...str(ascidat)## 'data.frame': 2585 obs. of 3 variables:

## $ id : chr "000CAT148_8.10.10_1" "000CAT228_8.10.10_1" "102PS0139_8.9.10_1" "102PS0177_8.28.12_1" ...

## $ site_type: chr "Reference" "Reference" "Intermediate" "Reference" ...

## $ ASCI : num 1.195 1.151 0.935 1.197 1.209 ...You can also view each dataset in a spreadsheet style in the scripting window:

View(cscidat)

View(ascidat)Other ways to import data

More often you will probably have an Excel spreadsheet to import. In the old days, importing spreadsheets into R was almost impossible given the proprietary data structure of Excel. The tools available in R have since matured and it’s now pretty painless to import a spreadsheet. The readxl package is the most recent and by far most flexible data import package for Excel files. It comes with the tidyverse family of packages.

Once installed, we can load it to access the import functions.

library(readxl)

dat <- read_excel('location/of/excel/file.xlsx')Summary

In this lesson we learned about R and Rstudio, some of the basic syntax and data structures in R, and how to import files. We’ve just imported some provisional data for the California Stream Condition Index (CSCI) and the Algal Stream Condition Index (ASCI) that we’ll continue to use for the rest of the workshop. These data represent a portion of the sampling sites that were used to develop each index. Next we’ll learn how to process and plot these data to gain insight into bioassessment patterns throughout the state.